If you're a buy-and-hold investor with a long time horizon, it's helpful not to focus too much on shorter-term total returns. Despite ups and downs from year to year, what really affects your results is the long-term average over time. In fact, if you invest a lump sum in a fund and don't make any additions or withdrawals, the total returns you ultimately earn will be the same regardless of the specific order of returns from year to year.

But if you purchase or sell shares, the timing of when those returns happen becomes more important. This issue is particularly relevant during the first few years before and after retirement. When you start making portfolio withdrawals, the value of your portfolio reflects both market performance and cash outflows, which can be a double whammy during extended market downturns.

In this article, I'll explain how the sequence of returns can affect the dollar value of your account. I'll also give some practical tips for mitigating sequence-of-return risk during retirement.

Background

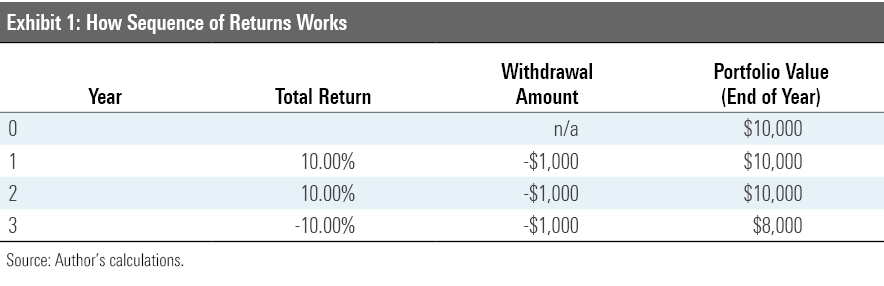

Let's start with a couple of simple examples to see how this works in practice. If you start with a portfolio value of $10,000, withdraw $1,000 per year, and earn total returns of 10% one year, 10% the next year, and negative 10% the third year, you'd end up with $8,000 by the end of the third year.

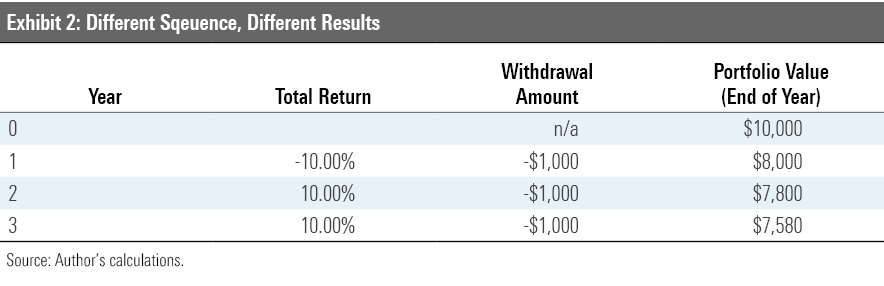

But if the returns happen in the reverse order, you’d end up with just $7,580, as shown below. Because the negative return happens at the beginning of the period (when more assets are in the account), it carries more weight in the overall results. At the same time, the portfolio doesn’t benefit as much in dollar terms from the two years of positive returns because there are fewer dollars remaining.

How Sequence of Returns Affects Portfolio Value Over Time

Historically, the U.S. equity market has had a seriously negative sequence of returns only a few times over the past 92 years: 1929-32, 1939-41, 1973-74, and 2000-02. These were all periods with equity market losses that lasted at least two consecutive years.

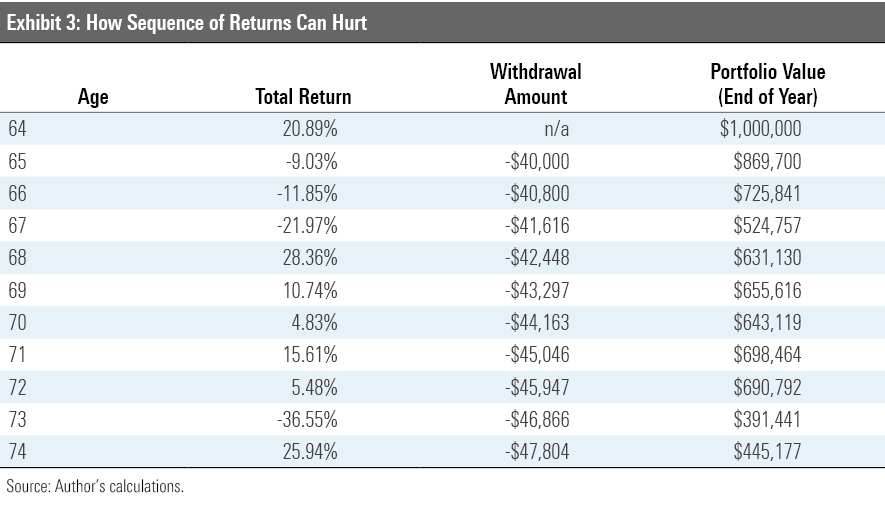

But it's worth being aware of this potential risk because of the havoc it can wreak for investors heading into retirement. The table below shows portfolio values for an individual who had the misfortune of retiring with an all-equity portfolio in 2000, just as the market was heading into a three-year downturn. This example assumes an investor retiring at age 65 with a portfolio worth $1,000,000. With $40,000 annual withdrawals (increasing by 2% each year to keep up with inflation), the portfolio’s value would have been nearly cut in half by the end of the third year. As a result, the portfolio didn’t benefit in much in dollar terms from the market’s rebound staring in 2003. Adding insult to injury, the portfolio would have suffered another major blow when the market dropped nearly 37% in 2008.

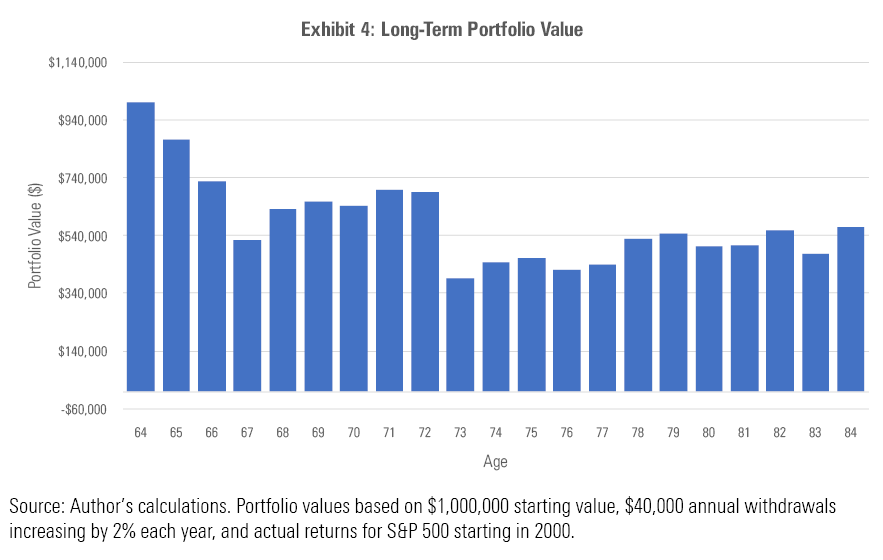

Because this sequence of returns was so negative, the portfolio never really recovered, as shown in Exhibit 4. By age 84, the individual’s portfolio value would be down to about $567,000, which doesn’t leave much cushion for extra costs late in life such as long-term care.

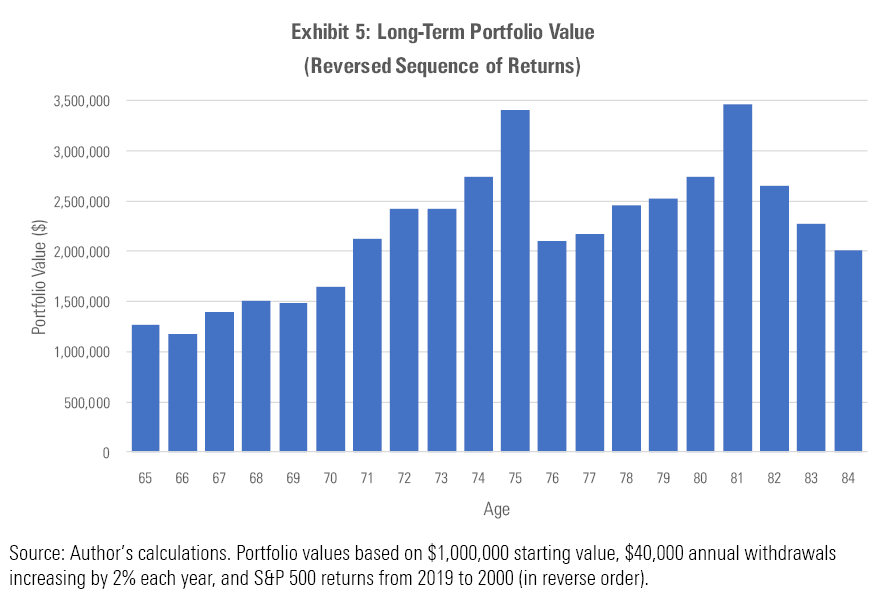

If the sequence of returns had been reversed, the picture would be far brighter. The chart below shows the portfolio’s value over a hypothetical 20-year period during which the S&P 500 earned the same returns as it did from 2000 through 2019, but in reverse order. By age 84, the portfolio’s value would be just over $2 million--leaving ample room for increasing the withdrawal rate, gifting to children and grandchildren, making charitable donations, covering costs for long-term care, or leaving money to heirs.

Mitigating the Risk

Of course, those are extreme examples; few retirees come into drawdown mode with all-equity portfolios. And in fact, adding a healthy stake in fixed-income securities is one of the best ways to mitigate sequence of returns risk. Although bonds can also be subject to risk from return patterns over time, returns typically fall in a smaller range and can help buffer some of the risk of an equity market downturn. Even individuals who had the misfortune of entering retirement right before the downturn in 2000 would have fared much better with a balanced portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds with annual rebalancing. The portfolio would have reached a low of about $791,000 after 2008’s market collapse but would have climbed back to $1.4 million by age 84.

The bucket approach that Christine Benz advocates is another way to mitigate the risk of an unfavorable sequence of returns. By putting at least one or two years’ worth of planned withdrawals in a separate cash “bucket”, investors can guard against the risk of being forced to withdraw assets during a market downturn. This also leaves the remaining portfolio better positioned to rebound when the market eventually improves.

Taking a more flexible approach to withdrawal rates can also alleviate the negative effects. There are many ways to implement this, including withdrawing a fixed percentage of your portfolio’s value each year, not adjusting withdrawal rates for inflation, or using a “guardrail” approach in which you reduce the withdrawal rate if it increases too much because of a declining portfolio value. We discussed this issue in more detail in our recent podcast with Jonathan Guyton, a financial planner and retirement researcher.

Finally, if you’re in the unfortunate position where you think you might run out of money toward the end of life, an immediate or deferred annuity can be a good solution. By pooling portfolio risk with other investors, annuities allow investors to earn a stream of guaranteed lifetime income. This provides protection against the risk of outliving your assets.

Conclusion

Sequence-of-returns risk is one of the more underappreciated dangers of investing. But understanding how it works can go a long way toward making sure your portfolio isn’t overly exposed to the potential downside.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5FNGF7SFGFDQVFDUMZJPITL2LM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EOGIPTUNFNBS3HYL7IIABFUB5Q.png)