As an investor, price declines for the securities you own, even if they are just paper losses, are generally unwelcome events. Still, in a generic, equally weighted portfolio of 20 stocks, a 10% drop in price for one individual holding results in only a 0.5% decline for the overall portfolio. Of course, portfolio diversification goes far beyond a simple “safety in numbers” concept. The goal of diversification is that the stocks in your portfolio won’t all move in tandem—some will zig while others zag, decreasing the risk for the overall portfolio.

Keeping Your Eggs in Different Baskets

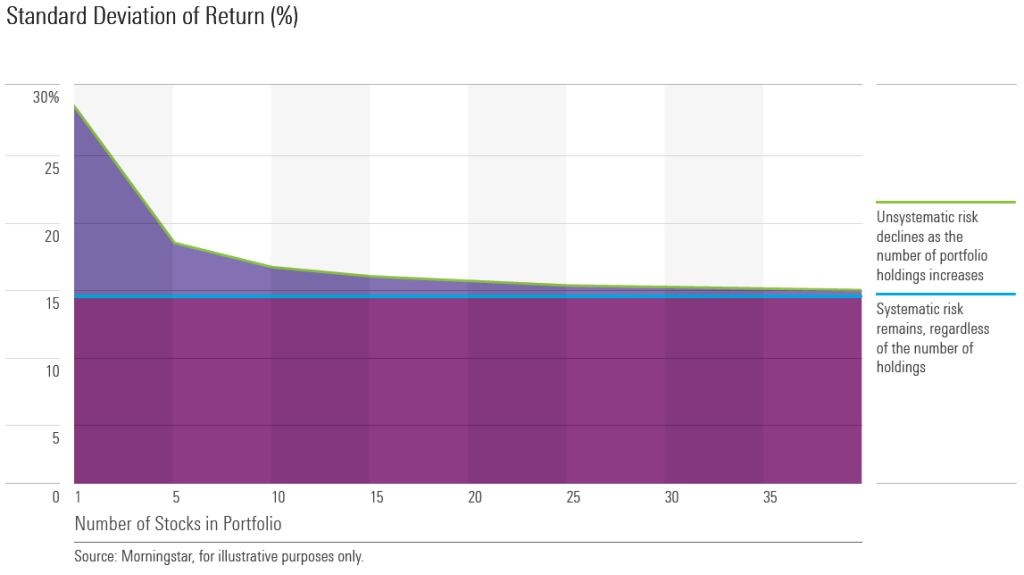

It’s important, however, to clarify which risks can be addressed via diversification: Systematic risk represents the overall stock market risk that investors cannot escape for the equity portion of their portfolios. Such risk can in theory be hedged via exposure to other asset classes. Yet in isolation, the market risk is still there, and hedging strategies often provide less benefit than expected. Unsystematic risk is the unique risk associated with an individual security, such as an unexpected roof collapse in a particular salt mine, which can be offset somewhat by assembling a portfolio of stocks. Diversification doesn’t provide a guarantee—it may reduce risk, but it doesn’t ensure a profit for investors or protect against losses in a declining market.

How many stocks are necessary to achieve sufficient diversification of this unsystematic risk? As you would expect, increasing the number of holdings in your portfolio generally decreases its volatility, as measured by the standard deviation of the portfolio’s returns. Yet multiple academic studies have shown that the incremental decrease in risk quickly falls off as the number of portfolio holdings increases. This reduction begins with a smaller number of holdings than you might think.

In 1968, John Evans and Stephen Archer concluded that a portfolio of 15 randomly chosen stocks would be no more risky than the market as a whole. In the 2002 version of Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management, Frank Reilly and Keith Brown point to studies that show that “about 90 percent of the maximum benefit of diversification was derived from portfolios of 12 to 18 stocks.

” More recent analysis by Morningstar Investment Management LLC confirms this general finding. James Xiong, head of scientific investment management research for Morningstar Investment Management, created the chart below by averaging the standard deviation of return for randomly selected groups of stocks, from a single holding to a portfolio of 40 stocks.

This research showed that the greatest reduction in the standard deviation of return occurs as the portfolio size increases from a single stock to 10 holdings. A smaller reduction is seen as the portfolio is increased from 10 to 20 holdings. Once you reach a portfolio of 20 holdings, the average standard deviation for the portfolio is only slightly greater than that of the overall market.

Several caveats are necessary, however. Xiong’s study used a broad universe of stocks, including small-cap stocks. If the universe had been limited to large-cap stocks, the correlation among those stocks probably would have been higher, due to the increased amount of index trading in recent years, likely increasing the standard deviation of the average portfolio. He also used monthly returns, which have a lower level of correlation than daily returns. Finally, his results, as well as those of similar academic studies, were based on randomly selected securities as opposed to actual security selection as practiced by either active portfolio managers or a rules-based investment approach.

Some research by Morningstar and others suggests, as Xiong noted, that block trading due to the increased use of exchange-traded funds and index funds has increased correlation among stocks to the point that a larger number of holdings is now required to gain the same level of diversification as in decades past.

Despite these overarching trends, Xiong found that average portfolio standard deviations were actually somewhat lower during 2011-15 than over the longer 1961-2015 period. But even if the lower standard deviations of the past five years are an anomaly, it seems likely that the curve illustrated in the above chart will persist: The vast majority of the reduction in unsystematic risk appears to come from the first 20 stocks in an equity portfolio.

The Case for Concentration

Nearly all equity investors desire some level of diversification. While letting it all ride on a single stock has the potential to produce amazing investment returns, it also has a huge downside, as many employees of Enron, who had most of their net worth invested in a single stock, would probably attest.

Given the math of diversification, is there a compelling reason to increase the size of an active stock portfolio beyond two dozen or so holdings? In our opinion, there probably isn’t, as owning 20-30 stocks will, on average, diversify the bulk of the unsystematic risk that investors face. Also, there are some very practical reasons to consider holding a couple of dozen stocks as opposed to hundreds. How many companies can you reasonably follow? A smaller number of holdings allows a portfolio manager to follow his or her individual investments more closely. Such a concentrated portfolio can also help a manager to focus on his or her highest-conviction ideas.

There is another potential downside to overdiversification, beyond the additional time and attention a larger number of holdings requires: By owning a large number of individual stocks and/or multiple managed products such as ETFs and mutual funds, an investor might diversify away virtually all of his or her portfolio’s unsystematic risk, leaving only the systematic market risk. However, such a portfolio is likely to come with greater investment costs (transaction costs, commissions, fund expenses, and so on) than a simple broad market index fund. In such cases, the higher costs of the investor-assembled “market portfolio” greatly reduce its chances of matching or exceeding the returns of a broad market index offering.

Different From the Market

If your investment goal is to exceed the total return of a market index, your portfolio must be different from that index. Otherwise, the most likely outcome is that you’ll trail the market index an amount roughly equal to your investment costs. A concentrated equity portfolio provides greater differentiation from the broad market. For any given time period, its performance is likely to be different from the broad market’s, even if its risk level, as defined by the variability of its returns, is similar. Sometimes these differences will be positive and at times they will be negative, but any short-term differences are generally not meaningful, in our opinion. We believe investors should focus on the long term—an entire market cycle—with the goal of a cumulative return that exceeds that of the broad market.

At the individual stock level, volatility isn’t always a bad thing for investors. If the price of a stock always remains close to its intrinsic value, it presents fewer buying opportunities for investors. Market sentiment frequently causes short-term overreactions to events that might have little long-term effect on the earnings of a company, presenting investors with an opportunity to purchase shares at a discount.

This concept of discounts to intrinsic value is a key principle of Morningstar Investment Management’s approach to portfolio management: the belief that combining a valuation discipline (buying stocks at good prices relative to their intrinsic value) with an emphasis on companies with economic moats (sustainable competitive advantages) will reduce the risk of permanent impairment of capital for an individual position. That’s a risk we believe should be of greater concern to investors than simple volatility.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5FNGF7SFGFDQVFDUMZJPITL2LM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EOGIPTUNFNBS3HYL7IIABFUB5Q.png)