U.S. economic data was much as expected on the week of 16, Jan. 2017, with inflation matching targets and industrial production looking seemingly better, which we believe is a bit of an illusion. We believe that inflation is still a very big problem for consumers, even if it doesn't get any worse from here. Wages aren't moving all that much faster than inflation anymore.

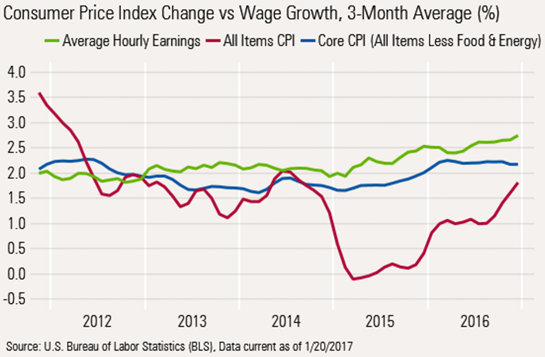

The market seemed to take in stride the 0.3% increase in the month-to-month headline inflation growth rate and 0.2% increase in prices, excluding food and energy. Indeed, this did equal the consensus forecast. However, we favor looking at year-over-year, averaged data, which shows a much less benign picture. For almost two years, headline inflation has run well below core inflation and hourly wage growth. That has been very beneficial for the consumer, who has been driving almost all of the economic growth in the U.S. recently. It is no coincidence that retail sales growth rates peaked early in 2015, about the same time the gap between inflation was at its widest level.

Unfortunately, the gap between headline and core inflation has closed considerably. The Fed could safely ignore inflation when the headline number was so far below core. Consumers think in terms of headline inflation, not core--you can't eat or drive with core inflation rates. The food and energy components amount to over 20% of spending. It doesn't make economic sense to ignore these components when predicting consumer behavior and recessions. That is why we pay very close attention to the red line above. Note that headline inflation has basically gone from zero to 1.8% over the last two years. Hourly wages growth has accelerated, too, but only from 2% to 2.7%, hardly putting the consumer in a better position, as many have suggested.

We always prefer to use monthly year-over-year data, averaged over a three-month period, as shown in the graph above. However, we could not resist looking at the single-month, unaveraged data to discern shorter-term trends. From December to December, headline inflation is 2.1% and core inflation is 2.2%.

The good news is that core inflation hasn't gotten a lot worse over the last year, as core goods have shown a slightly higher deflation rate than a year ago, and even core services have seen only slightly higher inflation in aggregate. The bad news is that the energy sector is likely to get even worse in the short term, especially what we already know about higher January gasoline prices. Also, food prices are acting very out of character and holding back overall inflation.

If food prices remained unchanged for the year (which seems like the best case), energy inflation holds to about 6%, and core inflation runs at the same rate as in December, full-year headline inflation would be about 2.2%. If energy increased by 10% instead, and food grew at 2%, total inflation would be about 2.8%. Of course, things could get worse if the energy producers' pact holds, if the weather turns cold, or if there are a few crop failures.

We don't think even 2.8% inflation would trigger a full-blown recession. However, our past work suggests that as headline inflation approaches 4%, recession cannot be very far behind. The 4% figure is relatively independent of the cause. The reason is that wages don't adjust nearly as fast as current prices.

Industrial Production: Still Not Much Change

Again, a lot of news outlets were excited by the 0.8% month-to-month increase in industrial production. However, a more sober view of the data suggests that the improvement in the manufacturing sector remains glacial at best. To get to that view, one needs to toss out the utilities and mining data that is so volatile and weather dependent that it doesn't do much for employment. On that basis, industrial production gained a modest 0.2% month to month, offsetting the decline of the previous month. However, we do acknowledge there have been more months up lately.

In a longer-term context, manufacturing did not rebound as strongly this recovery than in past expansions, and growth has slowly disappeared completely. Since 2011, manufacturing has grown just 1.1% per year, versus the 2.2% long-term average. Only motor vehicles and aerospace have performed at above-average levels this recovery. Now even those two key sectors have faded a bit.

In short, the industrial production was up maybe 0.2% month to month. At least it didn't go down I suppose. But the year-over-year three-month moving average that we like to use--for the last six, seven months that number's maybe gone from minus 0.2% to close to plus 0.2%. Hardly anything to get very excited about in terms of industrial production. We keep on saying things have bottomed, and we will take some credit for being right on that. But unfortunately, it hasn't been by very much, since it's moving up glacially.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5FNGF7SFGFDQVFDUMZJPITL2LM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EOGIPTUNFNBS3HYL7IIABFUB5Q.png)