We haven’t yet faced the sticky widespread problem of negative interest rates among conventional U.S. Treasury bonds that has beleaguered wide swaths of the global bond market (although some Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities have posted negative yields). There’s currently a heated debate about the long-term impact of negative rates on global economic growth, the financial sector, and investor behavior, and some of the early evidence isn’t comforting. But while the financial press has widely reported on the growing inventory of bonds across the globe trading at negative yields, few have explained clearly how negative rates actually work or why they’ve come about.

Observers have noted that owning a bond with a negative yield is akin to paying someone else to hold your money, but how? Although bond math is messy, it’s easy enough to understand that if you buy a plain-vanilla bond for $1,000 and it pays 10% per year (if only…), and you get your $1,000 back at maturity, you’ve made some money on the deal. But how can you lose money on a bond if it’s making regular interest payments?

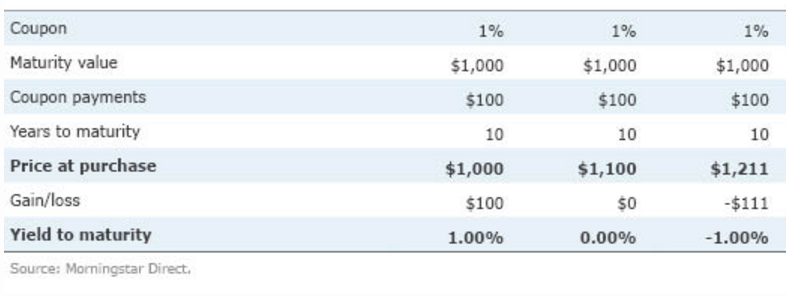

For starters, it’s important to remember that there’s a big difference between the very basic interest--or coupon--rate of a bond and its yield to maturity. The first one is a very simple expression of the payments a bond makes periodically, relative to its face value. On its own, it really doesn’t tell you anything about a bond’s overall return. A bond’s yield to maturity, however, is meant to provide a snapshot of its expected annualized total return, taking into account how much an investor pays for the bond, how much income it produces, and how much the investor gets back at the end. That’s crucial because whether you pay more or less than a bond’s face value up front will have a very important impact on what your ultimate yield to maturity, and thus your ultimate return, will be.

Examples mentioned presented side by side

Can a Bond Be Born Negative?

Those are examples of how transactions might look in the secondary market for bonds that have already been issued. You might wonder, though, how a government would structure a brand new bond when market yields are negative. It’s not necessarily an issue of a government simply wanting to sell a bond with a negative yield, of course. Somebody still has to want to buy it. As such, each government’s treasury generally prices its new bonds based on auctions whose prices affect, and are affected by, market rates.

As you might guess from the secondary market example, it all comes down to price. It remains fundamentally true that the more an investor pays for a bond the lower its return will go. So, when the market is trading such that a new 10-year government bond should carry a negative yield in order to match the market, the easiest path would be to sell new bonds without coupons---that is, zero-coupon bonds. Some European governments have done this. After all, in practical terms, you probably don’t want to ask a bondholder to send coupons back to the government. Unlike a normal zero, though, which is originally priced at a discount to its maturity value so investors earn the difference, an investor who pays more than the maturity value of a zero-coupon bond will get back less at the end of its term. And the deeper the negative yield, the higher that bond’s issuing price will be as well.

How Does This Even Happen?

Of course, the question of why an investor would agree to buy a bond with a negative yield is a messy one of its own, and there are several explanations. The most harrowing scenarios involve a dramatic economic slowdown and the deflation that would typically accompany one. In such cases, large investors without the luxury to hide billions of dollars under the mattress, might put it into “safe” assets that charge a premium for that safety.

In today’s environment, though, the most common causes involve central bank activity. When economies are sluggish and central banks are anxious to try and generate inflationary pressure (and economic activity and job growth), one of the first levers they turn to is to charge for commercial banks to deposit money with them overnight. That has the effect of pushing down short-term interest rates, and the impact typically ripples out to longer maturities depending on the market’s reaction.

The other big factor most at play these days is quantitative easing. Although we’ve experienced it in the United States, the practice has been massive overseas, including in Europe. In effect, central banks are buying longer-term bonds out in the market place and doing so in such large quantities that they dramatically pull down supply. Doing so--and telegraphing that more is coming--also encourages investors to try and ride prices up by buying bonds before the central banks do.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5FNGF7SFGFDQVFDUMZJPITL2LM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EOGIPTUNFNBS3HYL7IIABFUB5Q.png)