Cheap mutual funds tend to have higher returns. The less money the fund removes from its asset base, the more money is available for shareholders. You knew that already. But do you know the other two reasons to own lower-cost funds?

Live Long and Prosper

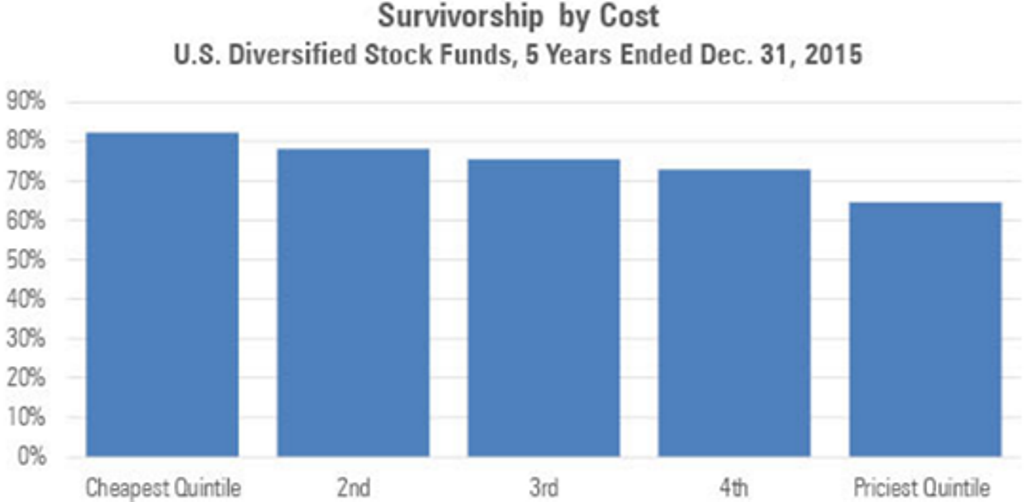

One is that cheaper funds live longer. Low-cost funds are significantly less likely to be liquidated or merged out of existence than are pricier funds. Consider, for example, the five-year survival rates of diversified U.S. stock funds, sorted into expense quintiles, through the end of December 2015.

That 18-percentage-point difference between the 82% survival rate for the cheapest quintile of U.S. stock funds and the 64% rate for the priciest quintile was no accident. The same pattern occurs across all asset classes. Sometimes the numbers are closer: With balanced funds, 82% of the lowest-cost funds survived, as opposed to 73% of the highest-cost funds. Sometimes the numbers aren't so close. But it's always a similar picture.

Fund liquidations (or mergers) are not disasters. No money is lost when funds disappear: Investors receive either the fund's quoted NAV (perhaps minus selling expenses) as proceeds or, more likely, the equivalent amount of a replacement fund. However, such an action can scarcely be regarded as a good thing. Funds that cease to exist are funds that failed.

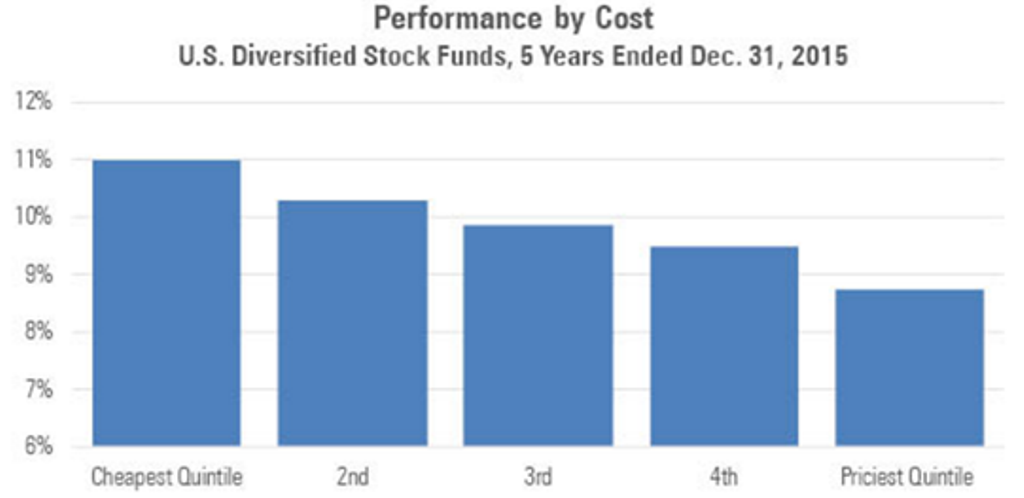

Most fee studies bypass these failures by including only those funds that existed throughout a certain period of time. (The problem is not data availability; it is instead the difficulty of explaining how to interpret the survivorship-bias-adjusted numbers.) This means that the usual argument for low-cost funds understates their merits. The chart below shows total return figures for those same quintiles of U.S. diversified stock funds.

As with survivorship rates, the total return conclusion is robust. The cheapest funds gained 10.98% per year, as opposed to 8.73% for the most expensive funds. Once again, the pattern applied to all asset classes. The equivalent figures for balanced funds were 6.19% and 4.35%. (Alternative funds were the one exception, presumably because of the statistical noise caused by the group's small membership.)

The effect was stronger than can be explained solely by the difference in expense ratios. That is, 2.25 percentage points of performance--a substantial amount indeed, for such a large pool of funds, sorted only by a single factor--separated the high- and low-cost funds, although their expense ratio averages were only about 1.5 percentage points apart. The same also held for balanced and sector funds, although not the other fund groups.

It's not clear whether this perk for cheaper U.S. stock funds will persist. As noted, the tendency for low-cost funds to fare even better than their expense ratios predict does not extend across types of funds. It may be that if we picked another time period, we would get another result. On the other hand, this is far from Morningstar's first fee study, and for the most part that's how the picture looks: low-cost U.S. stock funds outdo the expense disparity.

Well Used

Being likelier to survive, and being a healthier survivor, is more than enough to recommend low-cost funds. But there is a third, little-known justification for buying on the cheap: investor behavior.

Morningstar routinely compares funds' total returns to their dollar-weighted returns. The former--the standard method of measuring fund performance--does not consider a fund's asset size. If a fund gains 10% in total return when it is small, and loses 5% the next year when it is much larger, its total return for the two-year period is positive. Its dollar-weighted return, however, is negative. So on the whole, it lost money for its investors.

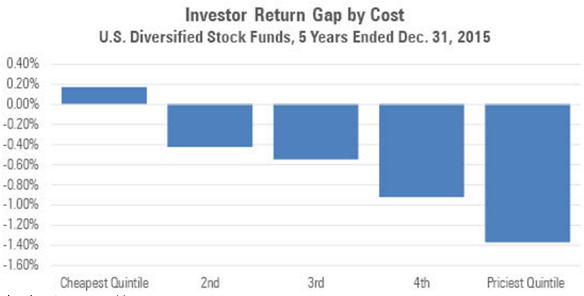

The difference between a fund's official, stated total return and its unofficial, dollar-weighted return (a statistic Morningstar labels as "investor return") is the return gap. A positive return gap means that a fund made more money for its investors than its total return would suggest, because investors used that fund wisely. On the whole, they bought shares before they rose and sold shares before they fell. A negative return gap implies the opposite.

In theory, if cheap funds had particularly bad return gaps, indicating that those funds performed well on paper but poorly for actual shareholders, one could argue that their benefits are illusory. They look as if they should be superior, but in practice, when people invest in lower-cost funds they don't enjoy improved results. In fact, investor returns indicate yet another payoff to low-cost investing

You read that right. Folks who owned the cheapest U.S. stock funds enjoyed a positive return gap from 2011 through 2015. The "dumb fund investor" turned to be pretty smart. Unfortunately, those who owned the priciest funds suffered the opposite fate. They were foolish enough to buy into a bad pool of funds. Then they misused those funds, costing themselves an average of 1.37 percentage points of dollar-weighted performance per year.

Putting together survivorship, fund returns, and the return gap leads to this: During the trailing five-year period, expensive U.S. stock funds were twice as likely to expire than were cheap funds. The funds that did survive gained an average of 7.36% for their owners (considering the effects of both total returns and the return gap), as opposed to 11.15% for cheap funds.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5FNGF7SFGFDQVFDUMZJPITL2LM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EOGIPTUNFNBS3HYL7IIABFUB5Q.png)