Q: If you have a very long time horizon, and won't need the money for 40 years, is there any point in diversifying into bonds or any other asset class that traditionally earns far less than equities? Is diversifying among different types of equities enough?

A: If you don't need the money for several decades, you are correct that you don't need to have a large allocation to fixed income. Because stocks, despite their volatility, are likely to outperform bonds over extended periods, the longer one's time horizon, the greater one's allocation to stocks should be.

But even if you have four decades until you retire, it never feels good to lose money. As Morningstar's director of personal finance Christine Benz explains, your risk capacity--how much risk you can tolerate given your time horizon--is often very different from your risk tolerance--essentially, your comfort level with short-term volatility. That's why a sliver of fixed income can be helpful, as just a tiny allocation to bonds can help tamp equity volatility in a portfolio without giving up too much upside.

Time Is on Your Side

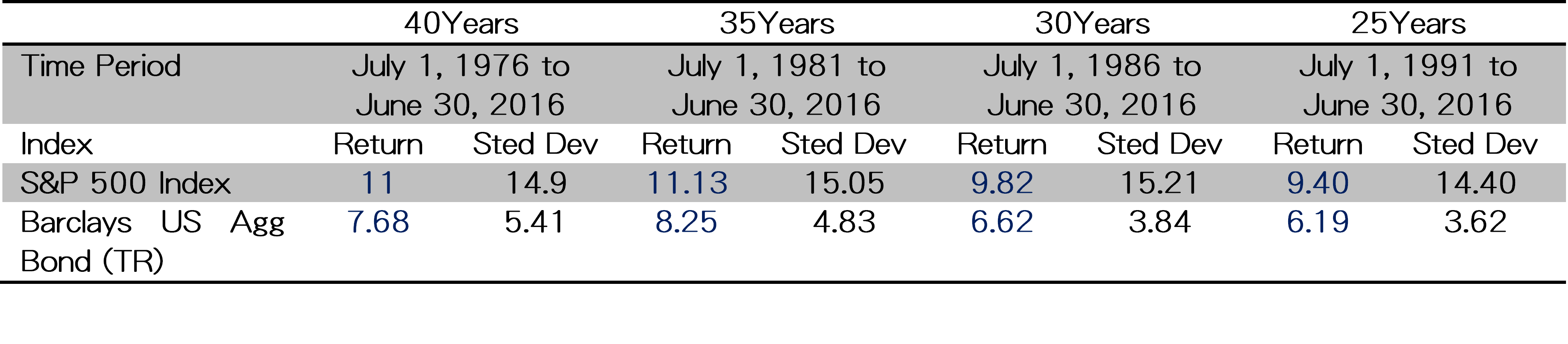

To assess the margin by which stocks have outperformed bonds, and the volatility of both asset classes, over long periods, we looked at the annualized return and standard deviation of the S&P 500 versus the Barclays US Aggregate Index over different time periods. The longest period we looked at is 40 years; we went back to 1976 because the Barclays (nee Lehman Brothers) Agg, which launched in its current form in 1986, has backdated data available through 1976.

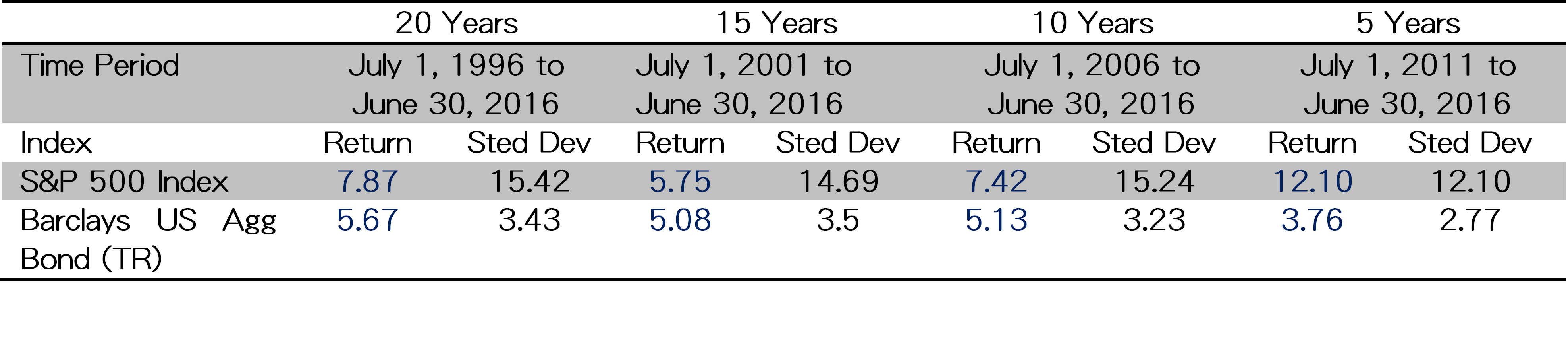

Over longer periods, such as 40 years, 35 years, 30 years, listed here, stocks are the clear winner. But because stocks are more volatile, and thus riskier, they should be expected to underperform over shorter time periods. However, periods shorter than 40 years can still be pretty long. What if equities don't compensate investors for their risks over a period that's as long as a decade? Maybe a decade and a half?

This is my story. Along with others in my cohort who were born on the cusp of Generation X and Generation Y, I'm one of those unlucky investors in the 15-year column. In fact, the S&P 500 has actually trailed the Barclays Agg over my holding period by 112 basis points, with more than four times the volatility as measured by standard deviation. Ouch.

It should be noted that I dollar-cost averaged--meaning I invested a bit of my paycheck every month--over this period, so this time-period-weighted return doesn't reflect my actual return the way it would if I had invested a lump sum at the beginning of the period and held the investment for 15 years. (I ran the numbers and I estimate that I actually improved my return by around 10% by dollar-cost averaging, through which I bought a greater number of shares when they were less expensive, and fewer shares when the price was higher.) Also, throughout this time period I also diversified my equity holdings into international equities, small and mid-caps, emerging markets, and more. But still--ouch.

Table1:Return & Standard Deviation to invest in stock and bond for 25 years-40 years

Source: Morningstar US

Table2:Return & Standard Deviation to invest in stock and bond for 5 years-20 years

Source: Morningstar US

Are Stocks Still Worth the Risk?

Over the past 15 years, many investors (myself included) haven't been as well-rewarded as they would have liked for taking equity risk. That has left some investors wondering if stocks are worth the risk at all. After all, the S&P 500's annualized returns have been a stone's throw from those earned by bonds, but with much, much greater volatility.

Without making explicit expected return prognostications for asset classes, I will say that I wouldn't expect the same pattern to continue over the very long term. The events that occurred in the market over past 15 years have been unique. The index lost 12% right at the beginning of the period in 2001, followed by a more than 22% loss in 2002. Though it got back on its feet in the following years, that 37% decline in 2008 really hurt.

As for bonds, the past 15 years was a period when yields were on the decline (and hence bond prices rose). In July 2001 the yield on a 10-year Treasury was 5.4% It's now around 1.4%. The effective Fed funds rates at these two points were 4.1% as of July 2, 2001, and 0.4% as of July, 1, 2016. Going forward, we're unlikely to see an extended period of declining yields given that rates are so low.

Finding the Right Allocation

As mentioned, a small fixed-income stake can make sense even for a very young investor, as it can smooth volatility a bit and reduce your portfolio's downside. (This can be especially helpful if you think you might find it hard to resist the urge to sell into the teeth of a downturn.) Just be sure that your bond allocation is small, or you risk giving up too much potential upside. In other words, even if you have an appropriate savings rate, you may still fall short of your retirement goal if you don't take on enough equity risk in your portfolio.

"A small splash of bonds can help tamp volatility in a big way," said Brian Huckstep, co-head of target risk strategies for Morningstar Investment Management. "When moving up from 0% of any asset class with attractive low correlation characteristics (which not all investments have), the first few percent often give you the biggest bang for your buck in volatility reduction. There is typically a decreasing marginal benefit for each incremental percentage of allocation until you hit an optimal allocation," he added.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5FNGF7SFGFDQVFDUMZJPITL2LM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EOGIPTUNFNBS3HYL7IIABFUB5Q.png)