Socrates Says

Little did I realize when writing Lessons From the Long Bull Market, published only two weeks ago, that I would so quickly be composing its bookend. (Technically the U.S. is not [yet] in a bear market, which requires a 20% decline from peak value. But permit me the verbal symmetry.)

In my ignorance, I had plenty of company. Just as few foresaw the long bull market, few anticipated the recent downturn. Sure, there are people who have predicted 17 of the last three sell-offs, and who will claim to have called this one, too. Nope. Huddling in a tent for several years straight, then leaping up to exclaim "Aha!" when the thunder finally sounds, does not a rain doctor make.

Besides, the skeptics got the causes wrong. The stock market was supposed to tumble because of the Federal Reserve's loose policies (quantitative easing!), which would spark inflation and sink the dollar. But inflation has remained low, oil prices have plunged, and the dollar is strong. In addition, Treasuries have rallied, whereas per the bears' inflationary thesis they should have fallen. This downturn has not followed the bears' script.

In short, the shorts were caught short. As of course were the longs, as the inability to know the unknowable is an equal-opportunity affliction.

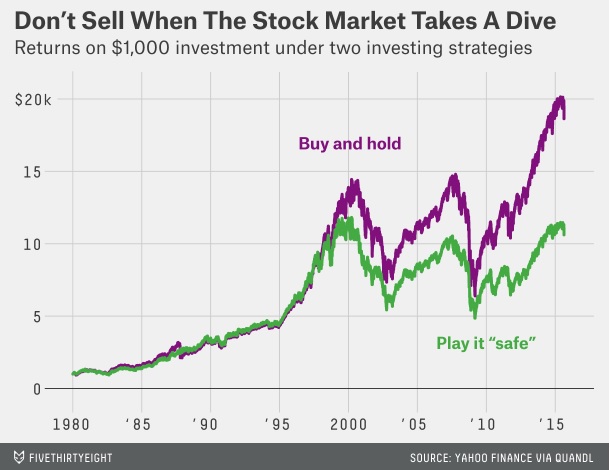

This collective fog makes post-crash interviews excruciatingly dull. Stay the course. Hold tight. Don't give in to your emotions. The bromides are mind-numbing. But they are correct, in that it is no easier to predict the market's recovery than it is its decline. This chart from FiveThirtyEight shows the results for a theoretical investor who moved to cash whenever stocks fell by at least 5%, then got back in once they recovered by at least 3%. Not pretty.

You know nothing. I know nothing. The person next to you knows nothing. From that realization leads the path to true (investment) wisdom.

The China Syndrome

China, too, is a bookend. When the revelry began in 2009, China was the toast. Now it istoast.

As I can attest from having attended several conferences in autumn 2009, institutional investors at that time strongly preferred glittering China to the fading markets of Europe and the United States. Yes, Chinese stocks in the previous year had been hammered along with other countries' equities--but they were roaring back, and unlike in the developed countries, the Chinese economy was booming. Safety lay not with stale, outdated asset allocations that had high weightings in the major stock and bond markets, but rather in creating portfolios that had big positions in both alternatives and Chinese securities.

Both of which have since been roughly break-even propositions. At least most alternative-investment funds have been relatively stable. China has gone nowhere, like a dog paddling furiously to keep its head above water. The MSCI China Index is currently at its 2009 level, but in the interim, Chinese stocks have suffered through two dozen sharp sell-offs. Meanwhile, the developed stock markets that were regarded as yesterday's news, for those who invested with a rear-view mirror and were oblivious to the changing of the times, have more than doubled their investors' monies.

China seemed to be an irrefutable proposition--an investment buoyed by the inevitability of history and supported by collective institutional wisdom. Both those beliefs were false. While China almost surely is destined to become the world's largest economy, its economic success is by no means guaranteed to lead to strong stock performance. There are many, many ways for corporate managements to squander--or appropriate for themselves--corporate opportunities. As for the collective wisdom of institutional investors, that on the whole is not greater than the collective wisdom of the unwashed masses. Among the rich or among the poor, herding is herding.

True Alternatives

The current downturn has pulled down all global equities. There haven't been notable exceptions, either among countries or sectors. Such widespread damage is generally the case with bear markets. On occasion, as with U.S. small-value stocks during the 2000-02 decline, there are places of refuge within the equity markets. (Thus, it makes sense to be well diversified among the various stock types.) But mostly, when one stock falls, they all fall.

There was a time when hedge funds offered true diversification, for those who had the means to own them. Back in the day, meaning before the mid-2000s, hedge funds behaved quite differently than the global stock markets, during both up and down periods. Not any more, though. For the past decade, hedge funds as a group have reliably acted as expensive versions of balanced funds, rising about half as much as stocks during bull markets, and declining about half as much through the downturns. Thursday's The Wall Street Journal reported that August has been no exception, with hedge funds losing about 5% on the month.

The surest protection for stock bear markets are gold and Treasuries. They won't always rise together through the downturn, as has been the case this month, but it would be odd indeed if they were both to fall. Whether that policy is worth its premium cost of low long-term returns is open to debate, but that gold and Treasuries (along with, perhaps, managed-futures funds) are the true alternatives is not.

Good Call

The beauty of Vanguard's cost-driven strategy is that as Vanguard gets bigger, its lever becomes longer. Those many fund companies that offer neither great products nor great prices will discover, as did Sears and Kmart before them [when encountering Wal-Mart], the real meaning of competition. They'll become Vanguard's lunch.

--Published in Morningstar FundInvestor, March 1996.

Bad Call

From Morningstar's Mark Noga: "Can you let me know the next time you write about how you should go 100% long equities so I can buy DXD?" (DXD is a leveraged short-stock fund.)

It seems that young Mark has not yet learned the meaning of the word "replaceable."

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5FNGF7SFGFDQVFDUMZJPITL2LM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EOGIPTUNFNBS3HYL7IIABFUB5Q.png)